It’s cold and wet outside as I sit here in an air conditioned metal tube, waiting for take-off. The winter travel season is upon us, and I consider myself fortunate to be able to experience the wonder of human achievement that is our air traffic system.

What we have managed to create dwarfs all previous attempts at a transportation network. We have massive, sprawling megaplexes devoted to aviation, where hundreds of thousands of passengers transit daily. The only thing that is more amazing than the technology we use to fly today is how limited most people’s understanding of it is.

The air traffic system is what glues our world together, and makes our massive…sorry, I think a bit of antifreeze from the A/C vent just dropped on me. Weird. Anyway. So the air traffic system is what makes our world possible – without it, the idea of “instant” would be a lot less, well, instant. Packages would be have to be shipped on the ground or on the water, and you can forget about traveling across the country for that business meeting or to see your relatives on short notice.

I don’t want to be negative by calling attention to this, but I should point out that this system will not last and it is not sustainable. We expend countless tons of fuel, not just on the aircraft, but on the aircraft’s support systems – the vehicles that tend to them, the cars that we drive to get to the airport; just think of how many airport employees alone are transiting each day to every airport in the world, so that we can get in these (admittedly pretty efficient) metal transport tubes that literally consume dozens of gallons per minute so that we can get to our destination on time.

The aircraft industry is built upon the assumption that our planets wealth is limitless, as is our time. We expend billions of dollars and several years, if not decades, designing each aircraft to eek out 10-20% efficiency gains that, while they do add up to many millions of dollars and gallons of jet fuel saved, they don’t really tackle the tough question; what are we going to do when we start to run into oil issues?

[2025 Update: The recent tariff-induced price spikes and supply chain disruptions have made these sustainability concerns even more acute, with major airlines now struggling to maintain operations amid fluctuating fuel costs and parts shortages.]

To understand the small steps that we’re taking, a bit of a primer on how the aircraft industry works would probably help. A specification is put out by a government or private agency for a new vehicle; this bid describes the mission that the buyer wants an aircraft to perform. Different companies, like Boeing, Lockheed, etc., all put in their bids, and these bids include projected performance figures, costs, timelines, etc. Basically, aircraft manufacturers…oo takeoff. This is the best part. You know that feeling you get in the pit of your stomach when you accelerate from 0 to 250 mph in less than 60 seconds? Freaking awesome.

Anyway, basically, aircraft manufacturers put together these bids and try to make them as attractive as possible. Sometimes they even build prototypes at their own expense, to prove the concept works. The winning bid is selected by the sourcing agency, and the aircraft’s actual development timeline begins. But these bids are put out by large companies and government organizations that aren’t necessarily thinking about things like a resource crisis – they’re just looking to carry a bit more freight at a bit lower price.

This is one way of doing it. The other way is when a commercial company, like Boeing, wants to update its current line-up of aircraft and begins development on the next generation of vehicles, like they have done with the 787 “Dreamliner”. This process is much like how you’d get any new product in the market; a need is identified (in this case, always more efficiency), development and marketing is initiated, and partnerships are made with interested airlines.

For the unfamiliar, Boeing touts the Dreamliner as the next revolutionary step in air transportation. For aviation fans, the Dreamliner represents a lot of interesting new technology, such as composite wing and fuselage structures, instead of the traditional aluminum, integrated entertainment, glass cockpit out of the factory, LED windows that dim so you don’t need a mechanical shade…lots of neat gadgets and engineering technology go into this aircraft. Take a look at the back of the engines on it and other new aircraft; the trailing edge has a bunch of little scalloped cutouts that improve engine effiiency and reduce noise. It’s pretty neat.

I am in no way trying to disparage the immense amount of work that Boeing put into this aircraft’s design, but in a way I am significantly underwhelmed. Do you remember earlier, when I talked about how the air transport system is unsustainable in its current form? Not to pick on the Dreamliner, but I really see it as a relatively minor step forward; it is, at its core, still just a tube and body aircraft that is meant to slot into existing global air transport systems. Yes, it is more fuel efficient than aircraft of comparable size, and this allows it to use less fuel and travel much farther. But these effiency gains are only within the 10-20% range for the most part.

This and other aircraft development programs do not get to the core of the issue; the fact that we expend all this time, money, and effort, to build a globalized, “always on” economy, without thinking about the practical possibility that we might actually run out of the fuel to run it. If every aircraft in the world’s fleets were replaced by Dreamliners (they won’t be – used aircraft vs. new aircraft are too cheap), we still would not be able to sustain the massive amount of consumption that we have today for more than 50 years.

Some analysis I’ve heard indicate that we may actually start feeling the oil pinch within the next 3-5 years. At that point, we’re going to see a drop in global trade and transport as oil prices climb, followed by a drop in oil prices, which will allow our economies to creep back up until we once again hit another ceiling and drop back down again.

Some of you may have noticed that current gas prices are lower than they’ve ever been in the last 7-10 years. What happened was this; they’ve been trying to figure out shale oil since the 70s. For the longest time it just hasn’t been profitable, but they spent that time mapping and understanding these shale oil reserves. But, now that prices have reached the point that mining shale is profitable, we’ve started digging into it, and we’ve started doing it an incredible clip. Some people have called this seeming abundance the era of the new “Saudi America”.

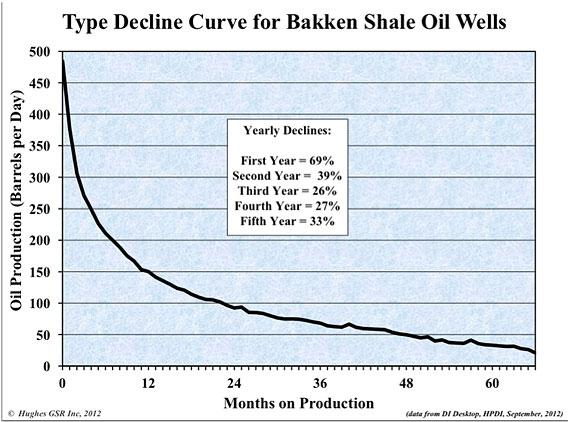

Unfortunately, shale declines very rapidly – you’ll get roughly 90% of each well’s total output within the first three years. So you get a huge drop in oil prices up front, when production is new; but to keep up production, we keep having to drill more and more wells. Luckily, we’ve spent the last 50 years mapping out these deposits, so we know where most all of them are. We’ve been drilling since about 2008 – if oil production was a bell curve; time-wise, we’re about a quarter of the way through depleting this resource.

So what happens next? Well, conventional oil is already in decline. Best case, we would be using shale oil to soften the fall. But now, we’re pumping oil out of shale reserves at an extreme rate, to keep our economy growing at the speed we’re accustomed to. This Slate article puts it pretty succinctly;

“At the high end of the estimates, predicted production from Bakken and Eagle Ford together amounts to perhaps a two-year oil supply for the United States at 2011 consumption rates. That’s significant but not a game-changer. Even if it were to prove possible to achieve production rates comparable to those of Saudi Arabia, that would only mean that we would deplete the resource faster and bring on an oil crash sooner.”

What we’re going to see is oil prices rising just enough so that it’s too expensive to maintain certain sectors of the economy. Individuals will experience this when they lose their job by getting laid off, or can’t afford to drive as often. Goods and services will climb slowly, and we will feel the crunch in a permanent recession. We won’t see gas prices instantly jump to $100 – the economy would simply grind to a halt. What we’ll see instead is slightly increased gas prices every year, until it becomes unnafordable for most people to drive. Unfortunately, more efficient cars exacerbate this problem, because in the grand scheme of things, they historically encourage people to drive more, since each trip costs them less than before. If you thought electric cars would help, well…guess what resource we use to make them?

[2025 Update: This prediction about shale oil has materialized largely as described. Production peaked around 2023 and has entered significant decline, contributing to the price volatility we’re experiencing today, further compounded by recent trade disruptions.]

So what can we do? There’s a lot of talk about the Singularity as some sort of end-all savior. There’s two things I have to say to this; 1) the multiverse helps those who help themselves, and 2) the very nature of the Singularity is that it is inherently unpredictable; just like what we’re going to see in at least the near future when all of these global changes really start to be noticeable (by the way, has anyone else noticed how crazy warm this winter’s been in Boston, compared to the snowpocalypse of last year?). I do believe in the Singularity; I do believe that it will bring prosperity and peace and amazing new technology. But we won’t know what’s coming until it’s already here.

I’m not saying the sky is falling, just that honestly there’s nothing we can do at this point. We have rushed so far into this problem without giving it the proper attention that an oil crash may be inevitable at this point. That being said, I wouldn’t panic and start stocking up canned tuna; whatever happens simply cannot be predicted. It is part of this brave new future that we are meant to live through. Our current civilization is so complex, so deeply entrenched, and so large that we simply can’t predict how things will break down. The best we can do is to be conscious of it now and work hard to start moving from our car-centric, oil-centric lifestyle to a more sustainable one.

What do I think is going to happen? Well, I choose to be an optimist. I think that since travel will begin to get so expensive, we’ll start to see a greater acceptance and growth in telepresence technologies – personal robotics, holographic and virtual reality meetings, and other future technologies that allow us to be somewhere without actually going there. Working from home may become the norm, and craftspeople may finally make a real comeback – you can already see it happening with the “made local” and the “Maker” movements. Air travel will diminish but not go away, but it may become very expensive for those few who do still fly. We may get our packages slower, but that may be ok because with the rise of local manufacturing, we might be able to build most of the things we need locally. Who needs to order a new pair of shoes when the microfactory or artisan group around the corner can produce a customized pair just for you? We will learn new skills to repair the things we have, rather than simply replacing them outright.

[2025 Update: The pandemic accelerated this transition to remote work and telepresence far faster than anticipated, proving that significant portions of our economy can function with drastically reduced physical travel. These systems are now providing crucial resilience during our current institutional challenges.]

[2025 Update: The development of microfactories and distributed manufacturing has progressed significantly since 2014, as detailed in my 2017 articles. These local production capabilities are now proving essential for communities adapting to supply chain disruptions and economic volatility.]

A return to community might also blossom in many cities around the world, especially in the United States, where the idea of the “block community” right now exists solely as a story told by the elder generations. When resources start to get tight, there are two options; fight or cooperate, and humans as a rule tend to want to cooperate rather than fight.

Lastly, if I am allowed to dream, I dream that we may be able to squeek through this resource crunch by deploying robotic mining operations throughout our solar system. By harvesting gasses, solar energy, and minerals from stellar bodies, we could see an uptick in production, rather than a shortfall. My company, Vogelmecha is a drone company and I have my sights set on space as a long term goal.

We are heading into uncharted territory, and I believe that it is really is up to our generation (I’m speaking of those who are currently aged roughly 18-35) to make sure our home remains a peaceful and beautiful place to live for the next 500 years. All our lives we’ve been told that we can save the world – and I think we actually have an opportunity to follow through in a way that hasn’t been seen since 1939-1945. This isn’t to say that the older and younger generations don’t have a place – we all need to work together to get through this. The experience of the old and the exuberance of the young is what will make or break this effort, so let’s welcome the future with open minds and fearless hearts. It’s our experience to live.

[2025 Update]

Looking back at this piece from December 2014, I’m reminded that systems thinking requires both patience and humility. Some developments I anticipated have arrived right on schedule, while others accelerated beyond expectation or emerged from unexpected directions.

The core thesis – that our centralized, resource-intensive systems would face increasing stress and require more resilient, localized alternatives – has proven sound. What I’ve learned in the decade since writing this is how critical the implementation details of these alternatives really are.

My 2017 articles on microfactories and local manufacturing explored the practical infrastructure needed to support the community resilience discussed here. Now in 2025, as we navigate a period of extraordinary institutional strain, these concepts have evolved from theoretical preparations to immediate necessities.

The challenges we face today – from workforce disruptions to supply chain breakdowns – are precisely the stressors this article anticipated.

My continuing desire is to focus on building these bridges between failing centralized systems and emerging distributed ones – creating technological and community infrastructure that functions regardless of institutional stability. The road ahead remains uncertain, but the path of resilience, localism, and adaptive technology still offers our best way forward.

~J

Hopefully, our government will not rip away most of the incentives that allow and encourage world class r&d to flourish and turn concepts and ideas into value-added and cost-efficient products and services, whether or not they prove disruptive and/or revolutionary as opposed to just useful and evolutionary. Without more cooperation between govt and business, saving the world will be a very tall order indeed.